BLOOMINGDALE -- Walter Trojan has never been particularly nostalgic for the war.

He had no interest in making the pilgrimage back to Normandy even when his friends in combat returned years later with their families. Memories kept him from going back.

"Nobody wins. That's what he's always said. Nobody wins in a war," his daughter Carole Trojan said.

His recollections of the Allied assault on Nazi-occupied Europe on June 6, 1944, and the beginning of the end of World War II, are fading. Now 97 and living with his daughter in a Bloomingdale town house, Trojan will quietly mark the invasion's 75th anniversary today as the diminishing ranks of survivors reunite at Normandy for what will likely be their last major observance.

What Trojan remembers most are the stories of men he's outlived, and in honoring them, he's sharing a lesson about his generation and what it really means to become a "Band of Brothers."

"Those are memories you can't erase," he said.

'A green city boy'

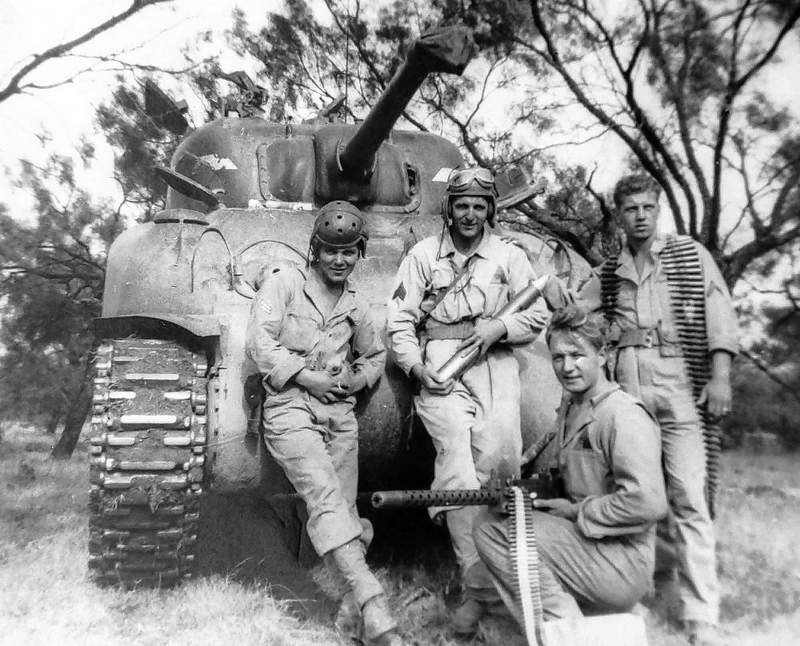

Trojan's daughter, Carole, preserves his relics from the war, a surreal, foreign collection of French currency, dog tags, a Nazi pennant, a card to his sweetheart signed "Wally" and some old photos.

In one, a young man is looking tough for the camera, dressed in his uniform, cigarette dangling from his mouth.

The 21-year-old was posing outside of his Army barracks in Texas in 1943 as a son of the Great Depression, a Chicago native who never finished high school.

Trojan looks at the photo and scoffs at his younger self.

"You talk about being a green city boy," Trojan said.

He grew up near the corner of Roosevelt and Halsted, raised by a mother who died of pneumonia in her 30s and a Polish father who worked as a machinist.

"During the Depression years, the boys, we played ball is all we did, played 16-inch softball a lot," Trojan said. "And I was a good athlete, swimming and everything."

Trojan joined the Army in September 1942 and reported to Camp Bowie in Texas, a training ground for other Chicago-area draftees.

"A lot of us were happy to join or go because our country was in trouble," he said. "We didn't have any work. If you had any work, it was cheap pay."

First shock of war

His memory of the battle for Omaha, one of the deadliest of the D-Day landing beaches, is hazy. But Trojan can still recall the chaos and brutality of D-Day, when 156,000 Allied troops launched the largest seaborne invasion in history.

"Those were desperate days. We just had a toehold," Trojan said. "We weren't sure our landing was a success. We were just in France, and Europe was a long way that we had to go."

Trojan said he drove a tank of the 745th Tank Battalion for the Army's storied 1st Infantry Division. The first tank off his barge never made it inland. Trojan suspects it struck a mine.

"But that was the worst I'd seen. For me, war started then," he said. "All five guys blown up."

When Trojan and his daughter watched Steven Spielberg's "Saving Private Ryan," she was horrified by the opening scenes and asked her dad if the film's most violent images were overly dramatized. He told her what happened at Omaha "was worse."

"You know you could be 20 foot from me, and your story would be different from mine," Trojan said. "That's how intermingled we were, and everybody had a different problem."

The war was ingrained in family life even though Trojan never talked about the "dark part," his daughter said. But the history of Trojan's battalion -- records provided by the First Division Museum in Wheaton and edited by Lt. Harold D. Howenstine and Tech Sgt. George E. Troll -- capture the hellscape at Omaha:

"There was a gigantic and terrible litter of wreckage as far as the eye could see when our first elements landed only a few hours behind the first wave," the authors wrote. "Submerged tanks and overturned boats and burned trucks and shell-shattered jeeps and personal belongings were strewn over those bloodstained sands. Bodies of fallen soldiers sprawled grotesquely in the sand or half-hidden by the high grass beyond the beach."

About two months after D-Day, the blast from a German shell tore off the right arm of Trojan's tank commander, Tom Nayder, a musician who played the guitar. Trojan tried to distract Nayder from his injuries.

"I got out of the tank to go over by him, and I don't think he knew his arm was off. They were putting him on the stretcher already. At that time, the medics followed very close," Trojan said. "And I said something to him. I didn't want him to look at himself.

"I said something to him like, 'Tom, you're going to be all right,' you know? His arm was gone. He was my best friend in combat up till then. That hurt me the most, losing him."

His battalion later advanced across Europe into Czechoslovakia until the surrender of Nazi Germany in 1945. The first person Trojan called when he got back to Chicago? Nayder, who had survived, but never returned to combat.

'We became family'

Trojan responds to recognition of his service with stoicism. When he used to live in a condo, he wished his neighbors wouldn't shove all the cards under his door for Veterans Day, thanking him for his service.

"There's lot of guys that will get no credit for nothing," he said. "They're still laying there."

But he isn't so gruff looking back on the Army brotherhood.

Without his right arm, Nayder learned to play the tuba and found Trojan a job as a sheet metal worker. They stood up in each other's wedding, and they were godfathers to each other's children. They went to battalion reunions until there were no longer enough veterans still around.

"We became family, guys I was with," said Trojan, who had three kids with his late wife, Irene.

During the '80s, another one of those guys, Jack Rakowski, would spend Christmas Eve with the Trojan family, bearing gifts. Rakowski died in 2004, and Nayder followed about a year later.

"Remember that, dad?" Carole Trojan asks. "All those years when Jack used to come dressed as Santa Claus? That was many years after the war. He didn't have to do that."

Her father doesn't forget.

"Those of us who had survived together, stayed close together," Trojan said. "We know we depended on each other's life."

At war and at home.